Shikha Mukerjee | Of Insiders and Outsiders: The Politics of Alienation

Language and identity politics threaten unity and freedom of movement in India

It would seem that the identity politics of being Hindu, the majority, and therefore the inheritors of the land that is Bharat, and the distancing of the largest minority community, it being made almost invisible and its exclusion from being represented, needs tweaking to sustain the politics of differentiation, categorisation and alienation. In case after case, states across India have begun reacting aggressively to the presence of “outsiders”, thus creating a new class of citizens, the “insiders”.

The Constitution’s freedom of movement and freedom to reside and settle in any part of India has acquired a political and social dimension it was never meant to include. In recent weeks, the outsider has become a target, a danger and unwelcome, if the goings-on in Maharashtra’s Bhayander, for example, are examined: a food stall owner was assaulted for not speaking in Marathi. The assault is vastly more significant than it seems.

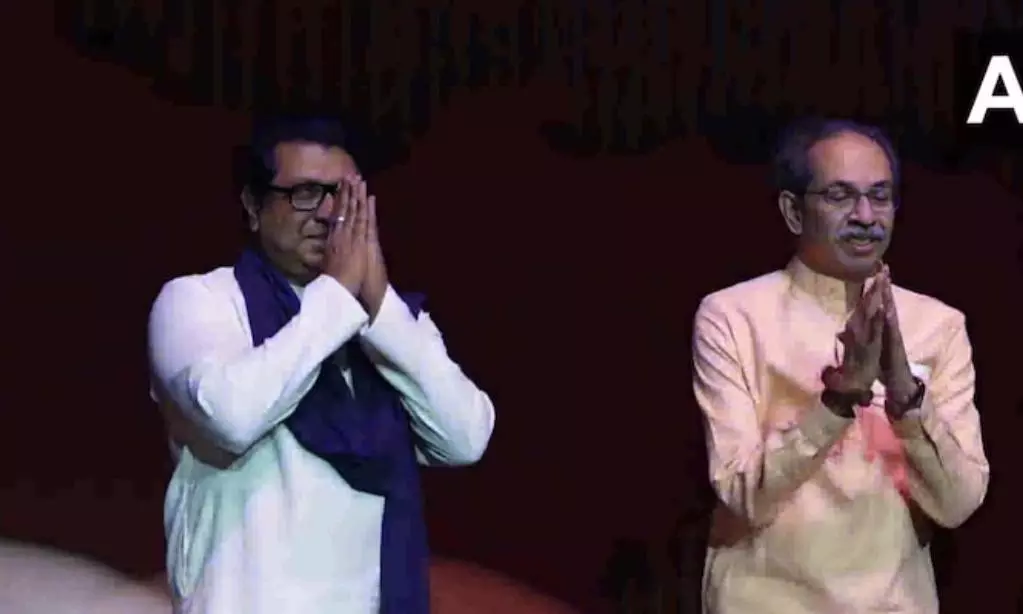

The revival of Marathi Asmita, Marathi Pride and the trope of the Marathi “Manoos” following the coming together of the two Thackeray cousins, Uddhav and Raj, with their separate organisations, is politically significant but also worrying. Will there be a renewal of the turbulence over identity and who belongs and who does not in Maharashtra, as happened when Shiv Sena founder Bal Thackeray launched his movement in the 1960s? Or a repeat of 2008, when the Samajwadi Party and the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena fought on Mumbai’s streets over “outsiders”.

Kolkata and, increasingly, New Delhi has its domiciled clusters of Odia language speakers. Heedless of Odisha’s reality, the state’s year-old BJP government has launched a drive to identify allegedly “illegal immigrants” in order to deport them to Bangladesh. Noble as this aim may be, the means used to verify have proved dubious.

If language is used as a filter of “foreign” and illegal, as Assam’s turbo-charged chief minister Himanta Biswa Sarma declared, he is on a politically slippery slope as two districts, Silchar and Cachar, are overwhelmingly Bengali-speaking. The presumption of illegality attached to a specific language speaker resident outside the home state, labelling the person an “infiltrator” is singularly mischievous. Linguistic politics is a very potent force and its use for short-term electoral politics is such a bad idea that Mr Sarma’s party bosses should be wary of permitting him to use it.

In line with the phobia that the BJP has nurtured over decades, the axiomatic confirmation that all Bengali-speaking, lungi-clad, presumably Muslims, must necessarily be illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, is the stuff that can be used commercially for a comedy script about mix-ups over identity. From Maharashtra, to Gujarat, to the Delhi-NCR area, Madhya Pradesh, Assam and Odisha, the Bengali speaker, even when he is from one of West Bengal’s 23 districts, has become a target for reckless discrimination.

The “othering” of Indians is dangerously destabilising politics, because it draws hostile lines of separation. What happens if the logic of linguistic discrimination is applied to other parts of India?

Will the Bengali-speakers settled by the Centre, the West Bengal government or the government of the then Central Provinces be deemed “outsiders,” “illegal immigrants” or “foreigners”? History of the kind that is based on facts, corroborated by documents, has its uses. Faced with the problems of refugee resettlement in the newly-created West Bengal state with a high population density, Dandakaranya, an under-populated area in Chhattisgarh, was selected as a great location for resettling the refugees from East Bengal/Pakistan after Partition. What happens if Punjabi-speakers coaxed to resettle post-Partition in Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Mumbai, Kolkata, Jammu and the Northeast or Madhya Pradesh when militancy ravaged Punjab, are deemed as “outsiders”?

The new wave of politically triggered alienation of India’s diverse ethnic, religious, linguistic populations, are not the sort of “reasonable restrictions” that the Constitution makers thought they had listed. The illegal immigrant is just one of the restrictions, it may be noted.

When people from the Northeast working, studying or training in other parts of India are jeered at, sneered, assaulted physically and verbally, the abuse is an offence. Those involved in such offences are obviously targeting the ethnically different population, which makes them suspect as potential racists. When the virus of attacks occurred in New Delhi and Bengaluru, freedom of movement was attacked and the victims were denied their rights.

In Bihar, the Election Commission issued a list of 11 identity papers it believes is foolproof and valid to separate the “outsider” from the “insider”. The “domicile” certificate as proof of everything, from citizenship to local address, is a bizarre requirement. By conflating citizenship with domicile, a word that is limited to specifying the local place of residence, the EC has revealed its incompetence in grasping the fundamentals; the domicile certificate, as the National Portal states, is a “certificate provided to the citizen by the government confirming their place of residence”. Given the current levels of hostility and suspicion about who is truly a citizen and who has acquired faked papers to establish a fake identity, how can the EC guarantee that all the domicile certificates it receives are issued only to citizens?

The purification of electoral rolls, which is the EC’s purpose, is not a new bug; it’s an old bug that has undergone a potentially dangerous mutation, much like the coronavirus that keeps evolving, sometimes more dangerous and sometimes less so. The “us” and “them” syndrome has invaded almost every public space and certainly private interactions, judging from the vast outpourings of trolls by underemployed persons on the social media, ranting about anti-nationals, critics, “Urban Naxals” and whatever label appears as offensive and hateful as possible.

The freedom of movement and “to reside and settle in any part of the territory of India”, which includes the right to settle almost anywhere if “reasonable restrictions” permit, is in danger of being jeopardized by the peculiar interpretations to the fundamental and guaranteed right to mobility.

And mobility, both out-migration and in-migration, are important marker of things political and social; it’s a marker of modernity, of inclusion, rather than exclusion of the stranger, of an opening up of the economy and opportunities for advancement, of a stable system of government and the strength and power of the rule of law that recognises the equality and rights of people in all their diversity.

Right-wing democracies worldwide are turning increasingly xenophobic. India, though it has an ideologically right-wing government, doesn’t have to mimic the West; it needs to guarantee freedom of movement, otherwise large sectors of growth, like construction, IT, services, health care, education, will collapse without “outsiders,” in cities like New Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Hyderabad, Bengaluru and the wheat lands of Punjab.