Shikha Mukerjee | Credibility at Stake Ahead of Bangladesh Polls in Feb

Youth, Islamists and the Army shape a volatile road to February’s polls

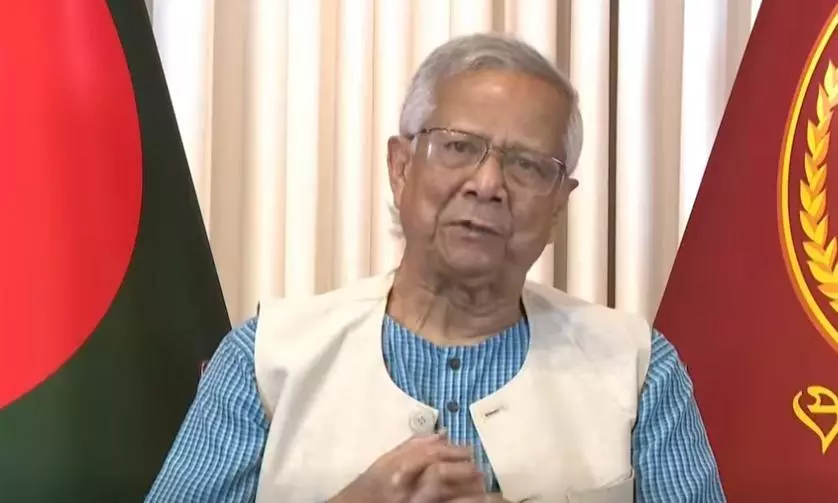

Across the Indian subcontinent, a spectre is haunting all the institutions which have the responsibility of holding free and fair elections. In Bangladesh, due to vote next month to elect a government to take over from the interim administration of chief adviser Muhammad Yunus, the poll body is suspected of “siding with fascism” by July Oikya, a platform of activists who mobilised to demonstrate outside its offices, and there is intense pressure building up, with flareups of confrontation between political groups linked with the mass movement that led to the ouster of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and the collapse of the Awami League government.

The confrontations between the Election Commission and the student groups, including the Bangladesh Nationalist Party’s Jatiyotabadi Chatra Dal and July Oikya, over the students’ union election at Shahjalal University of Science and Technology (Sust) this week will test the political environment before the general election. If the elections to the Sust students’ union are uneventful and the post-election scenario is peaceful, the Election Commission may feel confident that the general election, too, can be held without violence and accusations of “bias”.

Students and youth have been at the heart of the turmoil in Bangladesh since 2024 when the waves of protest and violent confrontations erupted over quotas for families of the liberation struggle martyrs led by the Students Against Discrimination, a broad platform that expanded and included radical and extremist Islamic groups like the Jamaat-e-Islami and Hefazat-e-Islam. The Sust students’ union election will be a precursor to the larger national elections on February 12.

The significance of students and youth, Gen Z, is obvious from the manner in which the BNP’s campaign face, Tarique Rahman, son and heir of the recently-deceased Begum Khaleda Zia, for whom the nation observed a three-day national mourning, has courted the mass movement that led to Sheikh Hasina’s hurried escape from Dhaka. “The movement was, in the truest sense, a mass uprising of pro-democracy people,” he had said. “1971 was about achieving independence, while the 2024 movement was about protecting that independence and sovereignty.”

As the party with the highest stake in the February election, the BNP is treading a careful and risky line, balancing between the goals of the party and other contenders, principally the Jamaat-e-Islami and its fluctuating number of allies — Hefazat, National Citizens Party and Inquilab Manch, fundamentalist Islamic organisations like the Inslami Andloan of Bangladesh, a multi-party cohort with theological differences, all of whom have set their eyes on getting a share of the pie as and when a government is installed.

Jatiya Oikya has targeted the poll body: “Those who give the Awami League, JaPa and the 14-party alliance a chance to participate in the election are siding with fascism. The Election Commission must understand the language of the people and cancel JaPa’s nominations immediately.” The BNP is worried and the Awami League, though banned from taking part in the election, has its reasons for manoeuvring for an outcome that will allow it to return openly to the political mainstream, instead of cowering in corners.

Volatile as this mix of political forces is, reports of Pakistan’s increasing presence and an Inter-Services Intelligence cell operating out of Dhaka could affect the election and post-election situation.

The Muhammad Yunus administration has worked at top speed to reopen links to Pakistan through trade, diplomacy and ease of travel agreements, which can be read in different ways, one of which is as a vanguard against any softening of position by any political party in Bangladesh towards India.

The campaign for the election is due to begin officially from January 22. The moment will mark an escalation of tensions, confrontations, violence and volatility. As the largest mainstream party with a history in heading a government that was installed after democracy was restored in Bangladesh in 1990 and elections were held in 1991, the BNP is not just the party with the biggest stake, it is also a party that needs to set the pace and tone of the campaign.

Tarique Rahman is riding a sympathy wave. He is also facing the toughest challenge in his interrupted political career, with 17 years spent in exile in Britain. He is the face of the BNP’s appeal to the electorate; he must navigate the claims within the party over how the leadership is to be managed in the post-election situation. As the face of the BNP, Tarique Rahman has not got down to brass tacks negotiations with Islamist political actors in Bangladesh nor with the Gen Z organisations with their liberal and Islamist leanings. However consistent he has been about expressing admiration for the leaders of the mass uprising, crediting them for leading a pro-democracy agitation and defending independence and sovereignty, should the BNP be in a position to form a government on its own or with allies, Tarique Rahman will need the sort of skills and experience he does not possess, as yet. There are at least three parties to forming a stable government post-election in Bangladesh: Muhammad Yunus, the Army and Gen Z groups, leaders and ardent activists attached to various Islamist organisations. For a stable government, the election must be perceived and approved by all stakeholders as both free and fair. And for that the Election Commission must be perceived and approved as impartial. If despite his assurances, Muhammad Yunus does not enable a smooth transition to a democratically elected regime, the situation in Bangladesh could rapidly descend into chaos; or, if the Army disapproves, regardless of how it does that or Gen Z disapproves by taking over the streets, the precarious situation in Bangladesh could spin out of control.

Complicated as the relationships are between the BNP and the parties that were once its allies as well as organisations like the Jatiya Party and independents, who are allegedly Awami League members masquerading as free radicals, the closer it gets to February 12, tensions are spiralling and on occasion have erupted in violence. There have been attacks and killings of Hindus in Bangladesh and complaints from the Bangladesh Hindu Buddhist Christian Unity Council of escalating violence and confrontations against minorities. The India-Hindu card is also an element in Bangladesh politics, that supposedly unifies the Islamist groups and parties and makes the Awami League an outcast.

Through all possible scenarios between now and the election, India can be either an interested observer or for its own domestic compulsions it can add rhetorical fuel to the fire, strengthening perceptions that it has an agenda beyond the national interest in what happens in Bangladesh.

Shikha Mukerjee is a senior journalist