Syed Ata Hasnain | As Dhaka Heads for Chaos, Challenge Grows for Delhi

The fall of Sheikh Hasina, the rise of radical Islamists, and the re-entry of Pakistan into Bangladesh’s internal affairs is not just a Dhaka story -- it is a regional turning point

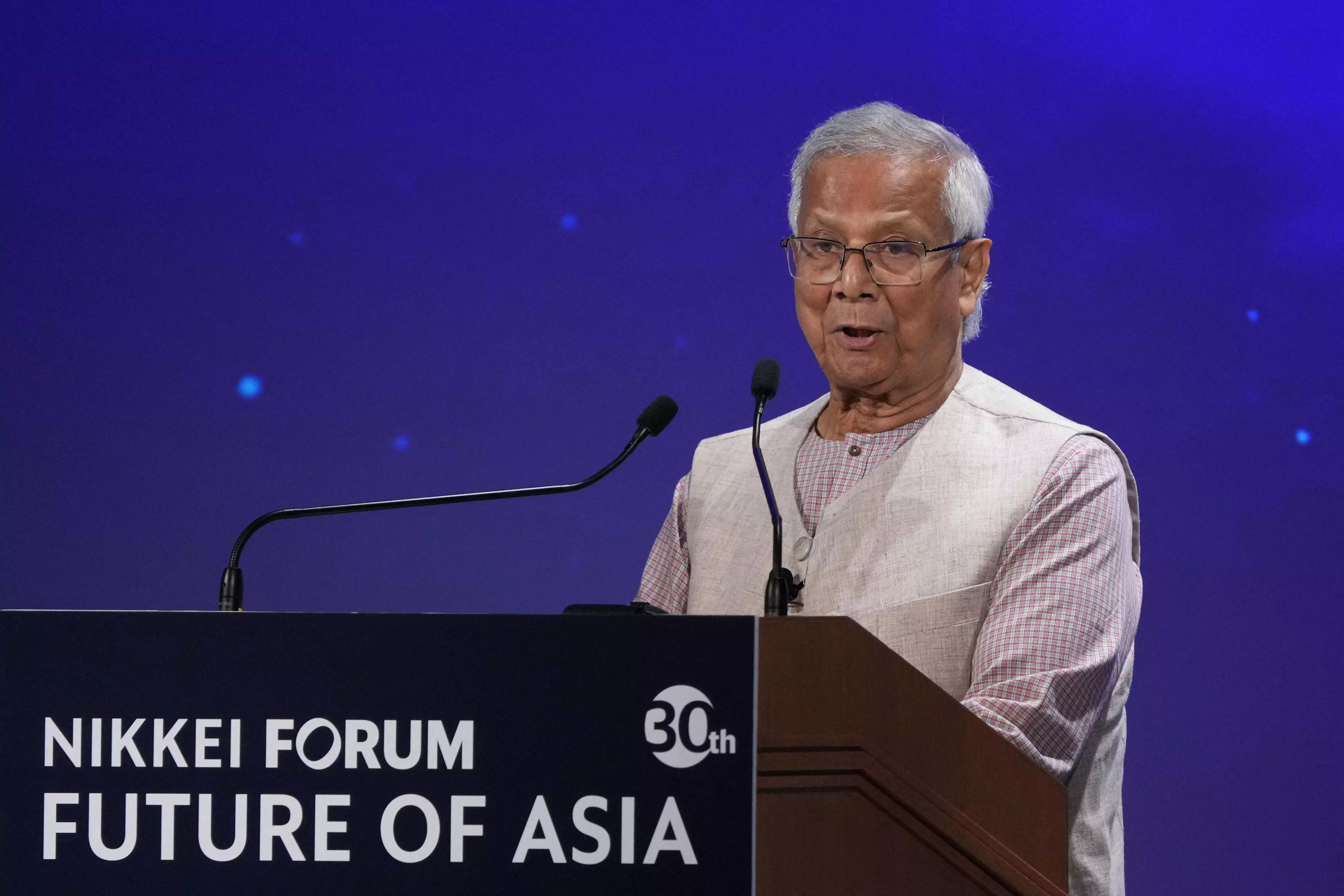

When history accelerates, the space between stability and collapse can vanish in months. Bangladesh today is a striking example. Once a regional partner committed to moderation, economic growth, and constructive ties with India, the country has veered dramatically off course. In recent months, the political order has been upended: Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, long viewed as a bulwark against extremism and a friend of India, now lives in exile in New Delhi. In her place, the reins of governance are with Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus -- an unlikely chief executive in a state increasingly dominated by radical Islamist forces.

Behind Mr Yunus’ technocratic image lies a deeper and more dangerous realignment of power. The ideological centre of gravity has shifted sharply. The Jamaat-e-Islami, once a fringe player tightly monitored by Sheikh Hasina’s government, now operates with impunity, setting the tone for governance and social control. Bangladesh’s already fragile secular consensus has collapsed. Reports of purges in the bureaucracy, censorship in academia, and a surge in Islamist vigilantism paint a sobering picture of a state captured by radical ideologues.

The political space is volatile. Mr Yunus finds himself under siege from multiple fronts. The Bangladesh Army is restive and reportedly suspicious of his authority. University campuses --long a site of political mobilisation -- are simmering with student protests, with many still loyal to the banned but still influential Awami League. Tension between these three power centres -- the radicals, the Army and the civilian street -- has reached a point where even minor provocations could spark major unrest.

I have often written that Pakistan never left Bangladesh, not even after 1971. Amidst this upheaval, Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) came looking for its moorings. The ISI has turned eastward to revive its old networks and stoke new fires. ISI operatives have made multiple covert visits to Dhaka in recent weeks, after initial visits by the hierarchy. Their objectives are clear: deepen Bangladesh’s Islamist tilt, revive insurgent linkages into India’s Northeast, and create an eastern theatre of instability that could distract and divide the Indian security forces.

This should not come as a surprise. The ISI has a long history of involvement in Bangladesh. During the 2000s, it cultivated elements of the BNP and Jamaat to allow safe havens for insurgents from Nagaland, Manipur and Assam. Arms flow through Cox’s Bazar, training camps in the Chittagong Hill Tracts and ideological indoctrination in madrasas was part of a broader asymmetric playbook. What was once disrupted during the Hasina years is now being quietly resurrected under cover of the current chaos.

The recent Operation Sindoor, however, has demonstrated India's political will and kinetic precision in targeting cross-border terror infrastructure. It should have sent ripples across the region. The doctrine of pre-emptive and retaliatory action cannot be ignored. The message of Sindoor -- that India will hold not just the perpetrators but also the enablers of terror accountable -- should have had a salutary effect on anti-India quarters in Dhaka.

China, too, has been watching closely and recalibrating its posture. Though traditionally focused on infrastructure and trade, Beijing now sees strategic opportunity in Dhaka’s disarray. Intelligence inputs suggest growing interest in dual-use facilities across northern Bangladesh, particularly at Lalmonirhat airfield, originally built during the Second World War but recently rehabilitated under a civilian pretext. Located less than 50 km from the “Siliguri Corridor”, any Chinese involvement there would carry serious strategic implications for India’s connectivity to the Northeast. While no formal military presence has been confirmed, the pattern echoes other precedents in the Indo-Pacific -- civilian infrastructure paving the way for security footprints. India must treat any such developments as potential “red lines”.

While overt diplomatic leverage in Dhaka is weaker today than during Hasina’s premiership, quiet channels -- especially military-to-military links -- can still be nurtured. For all its internal tensions, the Bangladesh military remains a nationalist institution with some institutional memory of its cooperation with India. Officers trained in Indian military institutions and having served with Indian military personnel in the United Nations, as also commanders who understand the cost of instability, are India’s best interlocutors now. Strategic engagement with these circles can help limit the damage from the state’s ideological shift. Army to Army; uniform to uniform, the language is the same.

Equally important is countering the psychological and narrative warfare currently being deployed by Islamist forces and their foreign patrons. The fall of Hasina is being framed not just as a political event but as an “Islamic revival” that delegitimises secularism and demonises India. If unchallenged, such narratives could radicalise an entire generation. India will need to reassert the value of India-Bangladesh historical ties, including the 1971 Liberation War, which remains a powerful emotional anchor among many citizens. The media has to be taken on board too.

In this, one under-utilised resource stands out: the Mukti Bahini veterans, or “muktijoddha”. These are respected voices, who fought shoulder to shoulder with the Indian Army to liberate Bangladesh and still command moral authority in parts of society. Many of them view the rise of Jamaat and the exile of Sheikh Hasina as a betrayal of the very ideals they bled for. India should quietly mobilise this community -- through scholarships, medical support and cultural outreach -- as an indigenous counterforce to radicalisation. Their memory of Indian solidarity in 1971 is far more persuasive than any other sentiment.

At the same time, India must pre-emptively address the threat of revived insurgency. While peace agreements and successful surrenders have brought relative calm to the Northeast, these gains are reversible. Any resurgence of sanctuary, ideology or arms flow from Bangladesh could reignite long-dormant conflicts. Central intelligence-sharing mechanisms would need to be recalibrated with the fresh eastern threat in mind.

Finally, a word of caution. India must resist the temptation to over-militarise its Bangladesh strategy. Hard power has its place, but so does strategic patience and multi-vector engagement. Regional diplomatic outreach to Asean, especially Myanmar and Thailand, could help coordinate responses to Rohingya radicalisation and arms smuggling. Quiet engagement with international financial institutions could pressure the Yunus regime to restrain the Jamaat’s worst instincts. India’s own civil society -- its universities, think tanks and cultural bodies -- should be encouraged to engage with Dhaka’s isolated liberal spaces to keep lines of empathy and understanding open.

The fall of Sheikh Hasina, the rise of radical Islamists, and the re-entry of Pakistan into Bangladesh’s internal affairs is not just a Dhaka story -- it is a regional turning point. India must treat it as such. India, however, can still shape events through engagement and creative diplomacy.