Manish Tewari | The Reasons Why India Needs An Open Budget

The historical origins of this secrecy are deeply rooted in the exigencies of colonial control and, even further back, in the political machinations of 18th-century Britain

The ritual of budget secrecy, shrouded in colonial-era mystery and enforced with a theatrical severity symbolised by the infamous “Budget Bunker”, stands as an anachronism in a 21st-century democracy striving for transparency and participatory governance. This tradition, wherein the Union Budget is opened only on the appointed day in Parliament, is less a pillar of prudent economic management and more a relic of a bygone colonial mindset.

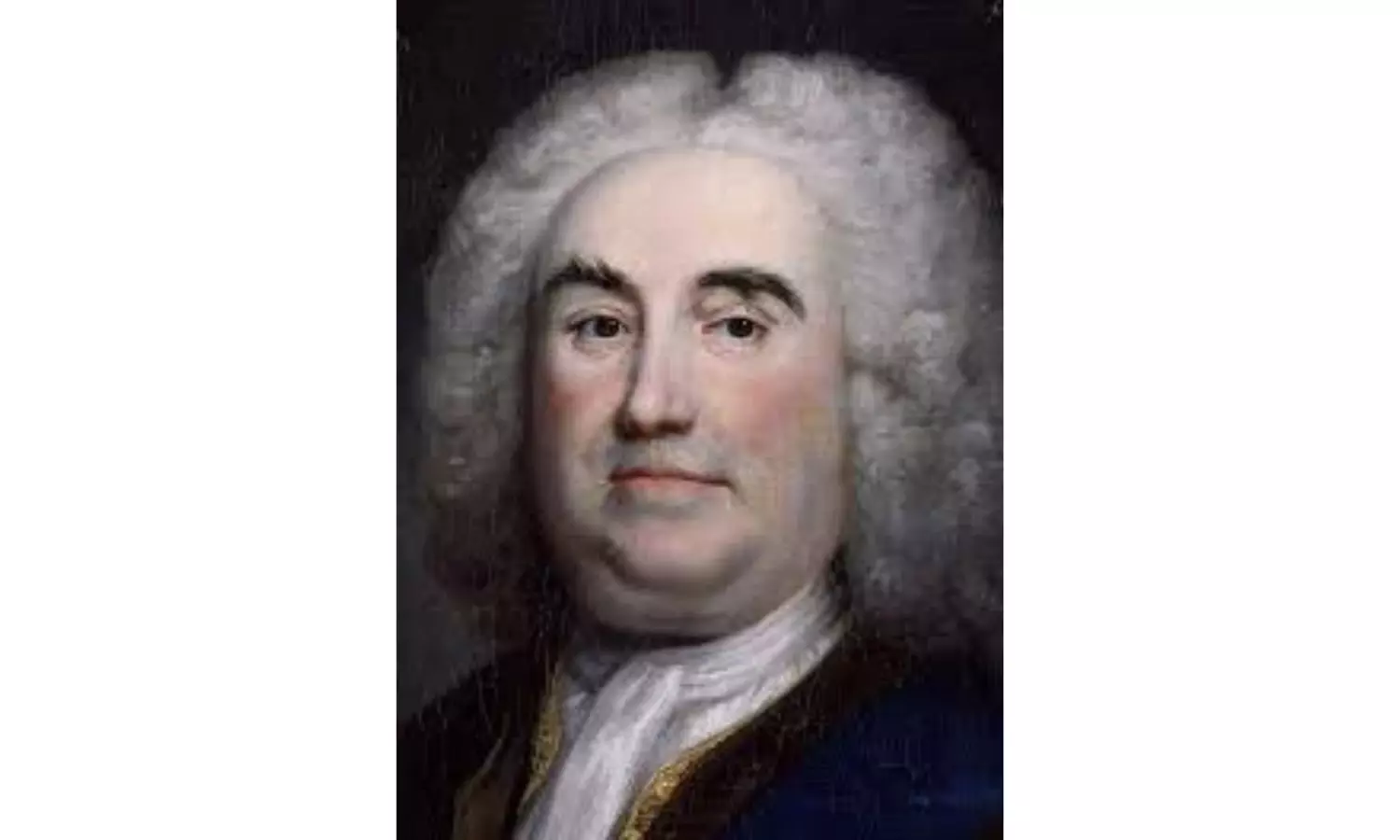

The historical origins of this secrecy are deeply rooted in the exigencies of colonial control and, even further back, in the political machinations of 18th-century Britain. The concept finds its progenitor in Robert Walpole, Britain’s first Prime Minister (also the Chancellor of Exchequer during his premiership). The very term “budget” entered the fiscal lexicon through satire and suspicion. In 1733, opponents of Walpole derided his tax proposals as a magician’s trick, publishing a pamphlet captioned “The Budget Opened” that framed the fiscal plan as a “grand mystery” revealed from a “bag of tricks”. Walpole and since then each chancellor used the secrecy of their financial proposals to outmanoeuvre parliamentary opposition and minimise public backlash rather than protect speculative market interests.

This practice was imported and intensified in British India, where the budget was a tool of imperial extraction, not democratic negotiation. The budget bunker of today’s North Block is the direct descendant of a colonial fortress mentality, a physical manifestation of the state’s insistence on monologue over dialogue.

The classic justifications for this secrecy are frail in the modern context. In an era of real-time data analytics, algorithmic trading, and global capital flows, the notion that a few weeks of clandestine preparation can effectively “surprise” the markets is naive. Instead, the sudden, big-bang release of complex fiscal and tax measures often induces volatility, as markets scramble to digest hundreds of pages of dense policy without the benefit of prior analyst scrutiny or phased debate. The real speculation it encourages is of the political variety: frantic media conjecture and lobbyist whispering campaigns that thrive in an information vacuum. Furthermore, the claim that secrecy prevents unfair advantage is hollow when one considers that sophisticated corporate entities invariably have greater resources to parse and react to the immediate budget announcement than the common citizen or small business, arguably exacerbating inequality of access rather than mitigating it.

Countries like Sweden, the Netherlands, and Germany operate on principles of open budget formulation. Key parameters – fiscal ceilings, major policy direction, revenue forecasts – are published and debated months in advance. Sweden’s Spring Fiscal Policy Bill, for instance, is presented in April, contains the proposed guidelines for economic policy which forms the basis of the forthcoming Budget Bill, which is presented in the autumn. Subsequent to when the Spring Fiscal Policy Bill is submitted to the Riksdag (Swedish parliament), a debate is held where the spokespersons for economic policy from the various political parties of the Riksdag participate. After the presentation of the final Budget Bill in the autumn, the Opposition parties submit their counter-proposals (shadow budget) to the proposals contained in the Government's Budget Bill, where the parties give an overall presentation of their budget alternatives. After considering both the Government Budget and the Shadow Budget, the Riksdag determines the maximum ceiling for expenditure in the government budget. Ergo, the limits or frameworks for the budget are determined, that is, how much money will go to the “expenditure areas”. The parliamentary committees can set different priorities to those presented by the government in the Budget Bill, and redistribute money amongst different appropriations in an expenditure area.

France, too, engages in a broad public and parliamentary discussion on the budget within a defined multi-year fiscal framework. The legislature becomes a partner in governance rather than a passive audience for an annual spectacle. Such openness correlates strongly with higher credit ratings, lower borrowing costs and greater fiscal sustainability – outcomes India desperately seeks.

The benefits of moving toward such a model for India are profound. First, it imposes a powerful discipline on the executive. Being required to publicly justify macroeconomic assumptions and policy choices months before the final vote subjects the budget to a crucible of expert scrutiny that can expose optimistic revenue projections or unsustainable commitments, thereby enhancing fiscal credibility and macroeconomic stability.

Second, it fosters substantive policy coherence. When major initiatives, be they a new welfare scheme or a defence modernisation plan, are outlined in a pre-Budget statement, the parliamentary committees can convene stakeholders, assess viability and evaluate alignment with long-term national goals, leading to more evidence-based legislation.

Third, and crucially, it would defuse the perennial controversy of politically timed economic packages. Under the current cloak of secrecy, large allocations for poll-bound states being announced on Budget Day are bound to attract criticism for using the fisc as an electoral tool. If these allocations are instead discussed as part of an open Budget framework, they could be evaluated against objective criteria of need, performance, and equity lending them greater legitimacy.

The path forward for India is a phased, intelligent move toward calibrated openness. The process could begin with a mandated Pre-Budget Fiscal Strategy Statement two to three months before the Budget Day. This document would be broad in scope but critical in detail: outlining the government’s assessment of the economic outlook, stating its medium-term fiscal targets, declaring its top-level expenditure priorities across key sectors, and clarifying the fiscal space available for new policy initiatives. This statement would then be referred to the parliamentary standing committees for formal hearings and a report. Simultaneously, a technical document on tax proposals could be shared with the Authority for Advance Rulings and a select panel of experts under strict confidentiality to vet administrative feasibility, leaving only the precise rate changes for announcement on the day itself. This model, a hybrid approach, preserves an element of surprise on specific rates to address legitimate market concerns while sacrificing none of the democratic imperative for scrutiny on the vastly more significant matter of public expenditure and fiscal strategy.

For a nation that intends to shed countless colonial legacies, captivity in the budget bunker diminishes the mandate of Parliament, treats the citizenry as subjects to be presented with a fait accompli rather than participants in a shared fiscal enterprise and perpetuates an opaque mode of governance. It is time to bring the sunlight of informed debate into the heart of our fiscal planning, for as Justice Louis Brandeis famously observed, sunlight is the best disinfectant. The nation’s fiscal health and the integrity of its democracy demand nothing less.