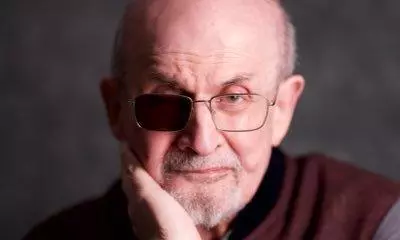

Farrukh Dhondy | My Life With Literary Indo-Brit ‘Legends’ Like Salman Rushdie, Kureishi & Tariq Ali

A personal glimpse into the courage, brilliance, and legacy of three “Indo-Brit” literary greats

“O Bachchoo, why do poets always say

‘They’ when they should be really saying ‘we’?

Don’t they know destiny has just one way

To dispose of all who happen to be?

One said: ‘We must love each other or die’

He realised that he’d made a mistake

He knew then that the word ‘or’ was a lie

The word ‘and’ should replace it for truth’s sake!”

From One Tree Mantri, by Bachchoo

Three “Indo-British” writers are probably the most prolific, talented, decorated and courageous individuals on the British literary scene of the past half century. All three are, though labelled “Indo-Brit”, really Pakistani by descent.

I mean Salman Rushdie, Hanif Kureishi and Tariq Ali.

I know them all as friends, of varying degrees and intimacy, and as contemporary fellow Indo-Brit writers. I’ve just finished reading Tariq’s second autobiography, entitled You Can’t Please All. And I have been re-reading the latest literary, extremely courageous output of both Salman -- his book Knife -- and Hanif’s Shattered.

I acquired, not bought, all three books together, cashing in a voucher which the bookshop chain Daunt gave me for chairing the launch of my friend John Williams’ biography of Trinidadian philosopher C.L.R. James. Daunt had an audience of fifty or so and our host introduced John and proceeded to say, “and we have with us today the legend…” I was seated in front of the audience, and I turned my head inquisitively saying “Gosh! Is Ulysses here?” The audience got it (Sorry, gentle readers), but today I would have said: “Who is it? Salman, Hanif or Tariq?” Deservedly, the “legends”.

I used the voucher for all three books. This, gentle reader, is not intended as even the slightest review of them. Salman’s book is about the stabbing he suffered in August 2022 at the hands of the maniac murderer while he was on a platform extolling the safety of writers in the United States.

Salman calls him “A” throughout the book, in which he describes his memory of the assault through which he lost an eye and suffered untold damage to his body and nerves.

The book speaks of his recovery, a deep testimony to the love of his wife and sons and, apart from characteristically fascinating pieces on, knives, love, pain, murder… you name it, it’s there-he writes an imaginary but elegantly, plausibly crafted interview with his attempted murderer.

Hanif’s account, dictated to his wife and his son, is about the paralysis he suffered after an unfortunate fall and damage to his spine. The account in Shattered, dealing principally with his hospitalisation, treatment, suffering and longings, recalls his distinguished life in writing and, unexpectedly if typically, contains chapters on sex, pornography, his dad. Salman has earlier written about his life after the fatwa from Ayatollah Khomeini urging his murder. My friendship with Salman began long before it.

When I was a commissioning editor at Britain’s Channel Four TV, Salman made a documentary on the real “midnight’s Children” -- famous people born on the 15th of August 1947. It was produced by one Jane Wellesley, a friend of his and descendant of the man who defeated Tipu Sultan and, subsequently, Napoleon.

Salman then made a documentary about an Indian who had discovered an American painter. He called it The Painter and the Pest. Salman then gave me a “proof copy” of The Satanic Verses, a rough blue-paper-covered manuscript and inscribed it, asking me what I thought would happen. I read it and said he’d be shuffling from TV studio to TV studio, arguing with Islamicists. Things turned out much worse.

I was, after the fatwa, a guest on a TV talk show recording in Manchester and was asked if I’d commission a film from the book. I said it had three strands to it and if someone wrote a screenplay I liked, yes, I would commission a film.

With me on this show was a pop singer called Cat Stevens who had converted to Islam and was wearing the white Islamic uniform and cap. With him was a fellow I knew as an Iranian bagman working for Khomeini. When I said I’d commission the film if the screenplay appealed, these two stood up on camera and shouted words to the effect of “kill him, kill him”.

After the recording, the producer asked me if I wanted to change hotels. I said, “Nah! Barking dogs!”

Even so, before I slept, I barricaded my room door with the writing table -- one never knows….

One of my interactions with the incredibly brave Hanif was when we were both finalists for the

Whitbread Literary Prize- he for The Buddha of Suburbia, and I for my novel Bombay Duck. Hanif won and, like Napoleon at Waterloo, I came second. When I met Hanif soon after and congratulated him, he said: “Nice title, Farrukh!” Ba….

And Tariq. A political history of Britain from the 1980s onward from the point of view of a Marxist activist. Unique!

After the fatwa, when Salman was under protection, Tariq invited him and me to his place for dinner. A police escort arrived to survey the place. While we dined, the cops went upstairs to wait in Tariq’s study, lined with Marxist tomes.

When the party was over, the chief of the protection squad came down and said: “Interesting books you have there, Mr Ali.”