Dev 360 | Reasons For Despair & Reasons For Hope | Patralekha Chatterjee

At school, children are told to celebrate India’s diversity. On the street, diversity is butchered with monotonous regularity

As one year gives way to the next, the ledger of despair and hope demands to be read. The savage killing of 24 year old Anjel Chakma, a student from Tripura, in Dehradun for objecting to racial abuse, is a chilling reminder of how fragile India’s promise of diversity has become. “I am Indian, what certificate should I show?”, were Anjel’s last words according to multiple news reports. It recalls the killing of Nido Tania in New Delhi a decade ago, mocked for his appearance and beaten to death by shopkeepers in bustling Lajpat Nagar.

At school, children are told to celebrate India’s diversity. On the street, diversity is butchered with monotonous regularity.

Anjel’s murder was not an aberration. His brother’s FIR describes drunk men hurling caste based slurs and attacking him with a knife when he objected. The police arrested five men; one fled across the border. This December, Christmas celebrations across several states have also been disrupted. Police records confirm incidents of vandalism, harassment and intimidation in Assam, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan and Delhi. Even vendors selling Santa caps were targeted. These attacks, alongside Anjel’s killing, point to deeper issues of discrimination against perceived "outsiders" in India and a growing unease with pluralism.

The phrase “fringe elements” is often deployed to contain the damage, but when disruptions recur across states, the pattern itself becomes the story. India has sought to draw international attention to heinous attacks on minority Hindus in Bangladesh, including two recent lynchings. Anger over the lynching of garment worker Dipu Chandra Das in Bangladesh’s Mymensingh is legitimate. But moral consistency requires us to apply the same standard at home. If we demand protection for Hindus there, we cannot remain silent when the minorities are targeted here.

Intolerance at home is also counter-productive when the country seeks to position itself as a leader of the Global South. Credibility abroad depends on consistency at home. If pluralism is undermined domestically, India’s moral case internationally is weakened.

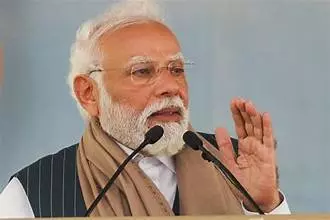

It is hard to miss the irony in the headlines running side by side. It is entirely proper -- indeed welcome -- that India’s top leaders, from Prime Minister Narendra Modi to ministers Rajnath Singh, Nitin Gadkari and J.P. Nadda, marked Christmas with messages of harmony, peace, and goodwill drawn from the teachings of Jesus Christ. Yet the poignancy of this season lies in the distance between these words and the lived experience of many citizens in the very same week.

According to the United Christian Forum, 834 incidents of violence against Christians were recorded in 2024, up from 139 in 2014. As of November 2025, the forum had documented 706 incidents. Muslims and Kashmiri students were targeted in parts of the country following the terrorist attack in Pahalgam.

Communal harmony was not the only casualty of 2025. The second crisis was structural youth unemployment amid impressive macroeconomic numbers. GDP grew briskly, exports performed well, gold, and silver shares hit record highs, but the jobs created were almost entirely low quality -- informal, gig based, precarious. Analysts have repeatedly warned that this mismatch is squandering the demographic dividend India has long touted.

The consequences are accumulating quietly. When skilled young people see no stake in the formal economy, the loss is not only economic; it is social and political.

These wounds have been deepened by environmental failures that make sporadic headlines but carry profound long term ramifications. Delhi’s winter air turned toxic once again, with AQI frequently breaching severe to hazardous levels, driven by vehicles, construction, industry, stubble burning and winter

inversions trapping pollutants. The Aravalli hills, India’s ancient ecological barrier against desertification, became a flashpoint when a Supreme Court ruling adopted a narrow height based definition, criticised for excluding vast tracts from protection and opening them to mining and real estate. Protests erupted, warnings of accelerated groundwater depletion, dust storms, and Thar desert encroachment into fertile plains. These lapses exacerbate health burdens on the young and poor, widen regional inequalities, and undermine the sustainability of growth.

And yet, amid the many reasons to despair, there are reasons to hope. Photos on IAS officer Uma Mahadevan Dasgupta’s X handle show children reading newspapers and solving crosswords in Karnataka’s rural public libraries. During a recent family holiday, I wandered around a tribal hamlet in Gopalnagar in West Bengal’s Birbhum district, a stone’s throw from Tagore’s Santiniketan. A teacher in a spotlessly clean primary school in an Adivasi (Santhal) hamlet in Gopalnagar told me the children got eggs, and sometimes meat and fish as part of their midday meals. I saw a boy picking wild flowers to decorate his classroom for Christmas. The happy faces of children emerging from the primary school in this remote tribal hamlet made my day. These protein rich extras (eggs, sometimes meat/fish) come from state funds supplementing the central PM POSHAN midday meal scheme, where the Centre and states share costs 60:40; the Centre provides foodgrains and norms, while states decide menus and add items like eggs or fruits. I have never quite understood the politics of eggs in this country where millions of children remain under-nourished but it reminded me of the power of targeted efforts.

Besides West Bengal, of the 36 States and UTs, 16 -- Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Kerala, Mizoram, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Assam, Telangana, Uttarakhand, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Ladakh, Lakshadweep and Puducherry -- also provide eggs in midday meals. Uttarakhand, Odisha and Assam are possibly the only BJP ruled states to serve eggs.

I was also lucky to be in Kolkata end-December. Christmas here transcends cliches -- beyond glittering Park Street and plum cake, it becomes a true people’s festival, crossing religion and class: Parvati, a Hindu domestic helper who celebrates Durga Puja with equal ardour, told me about her Christmas festivities: the family feasting on mutton curry, fish head dishes, a small cake and a granddaughter delighted with Santa caps and reindeer headbands. In a state scarred by political violence, this platforming of pluralism is not to be sneered at even if there is much to criticise otherwise.

Similar flickers are visible elsewhere: When space is given, Indians build solutions bridging economic and social divides.

As we kickstart 2026, we must not let loud headlines always obscure slower developments and flashes of joy. We need these micro boosters to temper macro realities when darkness falls. In hyper-polarised India, many ordinary citizens continue to practise inclusion and initiative.

The urgent question for the new year is whether leaders and citizens will match the examples of inclusion.

India’s future hinges on healing cracks caused by frayed harmony, stalled futures, degraded environment. Whether it can repair these cracks before they widen will define not just 2026, but India’s larger unfinished story.