Can Build The Human Genome in 20 Years: Adrian Woolfson

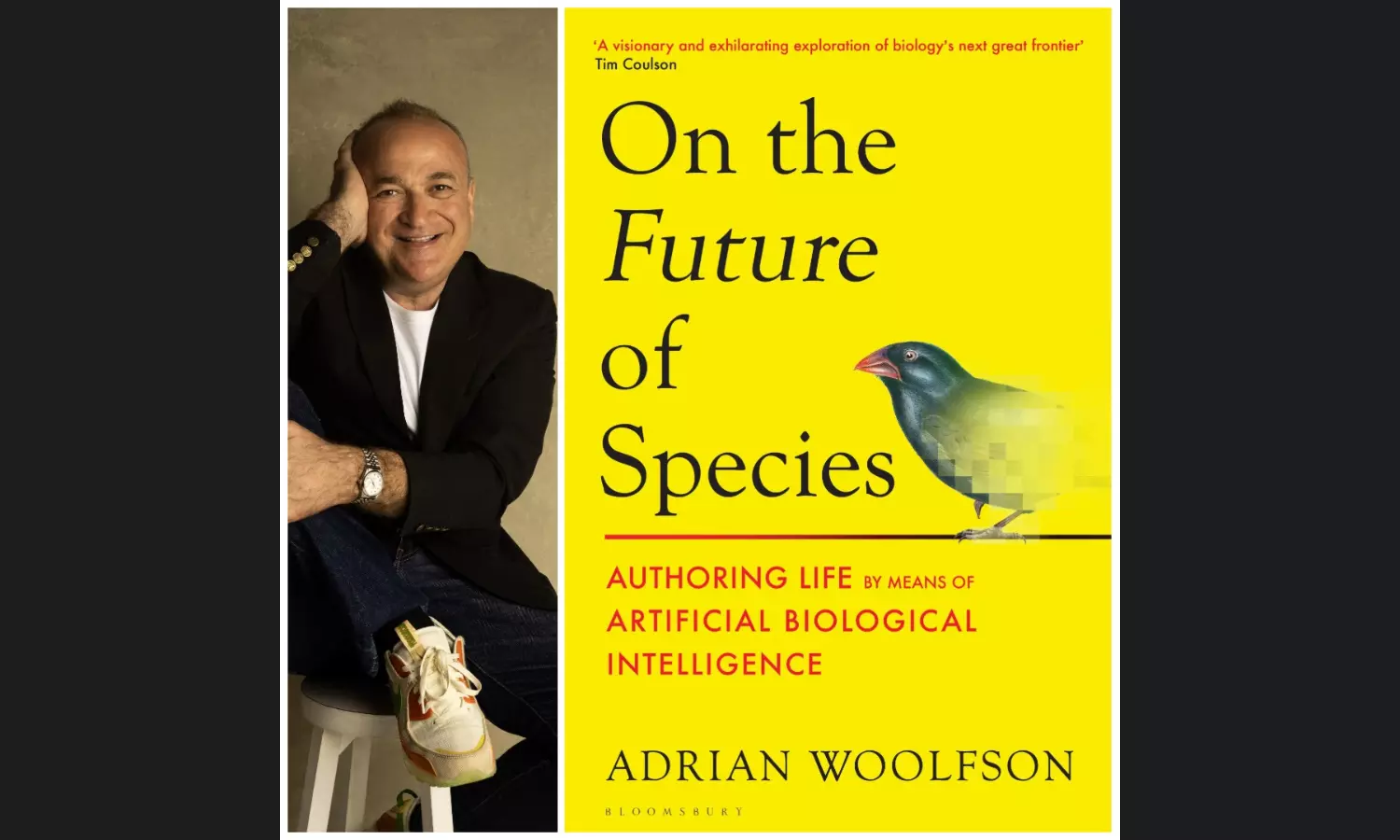

ADRIAN WOOLFSON, scientist and founder of Genyro, has authored a brave new book, 'On the Future of Species'. Here, Woolfson examines with SUCHETA DASGUPTA the future of humanity in a world of AI and ABI

What is the difference between AI, ASI and ABI, artificial intelligence, artificial super-intelligence and artificial biological intelligence?

Yes, I can. So artificial intelligence is a type of artificial intelligence that can be used kind of generically across all domains. And artificial general intelligence is a type of AI which hypothetically meets the same kind of level of complexity as human thought, or maybe even slightly exceeds it. Artificial superintelligence, ASI, is a level of synthetic intelligence, machine intelligence, which exceeds human capabilities.

And I came up with the term ABI; that's the term artificial biological intelligence. And the reason I came up with that term, it's my term, that's why you may not have heard it, is I felt that when AI gets applied to biology, something special happens, which has never happened before. And that deserves a new term. And what I mean by ABI is the ability to look at a genome sequence you've never seen before and say, ah, that computes a rhinoceros or that that makes an elephant. And that's the kind of recognition part of it. Then there's a generative part. So, you say to me, Adrian, build me a new type of maize that's drought resistant or a new species. And I say, sure, here's the genome sequence that does that. We'll get rid of this disease and this chromosome. That's the generative component of ABI. Then there's a constructive component, which means being able to build that DNA that you imagine, and fourth, to boot it up into a living thing. So, it's the recognition, generation, construction and booting up. That's ABI. AI as applied to biology. An AI that can unpack the rules of biology like a language and use those, use the grammar, if you like, of the language to write sentences in the language of biology and whole genomes which are like books effectively.

That's a great answer. Thank you for that. But governments around the world have put curbs everywhere on this kind of research involving stem cells, for instance, or cloning. Is it going to change in the short term?

Well, you know, it's not everywhere. I mean, the stem cell research, for example, is still going on in many places. The clone, when you say cloning, I'm assuming you mean cloning of humans, because people are cloning their dogs right now, right? But what I'm doing is fundamentally different to all of that.

You know, what I'm, the science of generative biology involves designing life on a computer and then literally writing it out as if you're writing Dostoyevsky or E.M. Forster or, you know, Arundhati Roy. You know, you're literally writing genomes as if they were written text.

So this is very different to anything that's come before. It's very different to gene editing, for example, because gene editing, many of your readers would have heard of CRISPR, for example, right? And gene editing involves redlining. Essentially, if you imagine a genome as a document, when you gene-edit, you're just redlining it.

You know, you're changing something that already exists. But with generative biology, you're taking a blank piece of paper and you're writing a new story for the first time, which doesn't have to be limited by what's come before.

So, do you think that the governments will be open to accepting it, or will they try to regulate it?

Well, it's a good question, Sucheta. And in fact, the way it turns out is that the governance is, you know, barely there as we speak, because the technology has kind of happened so quickly that nobody's actually kind of kind of sat up and said, oh, you know, what is this new technology? There doesn't seem to be much awareness of this and it was one of the reasons I wrote my book on the future of species because I wanted the general public to be aware that there is a new show in town and this show is quite an important one. It's one that can stand side by side with natural engineering, which is evolution by natural selection, and actually author life in a new way as a kind of collaboration between AI, which is artificial intelligence, and humans, which is natural intelligence, right? So, all of a sudden, life on Earth has two authors instead of one. Evolution and us.

Can you tell us a little bit about yourself and what started your interest in genomics and generative biology?

So, my background is I’m a medical doctor. I trained in Oxford in England, and then I did a PhD with the Nobel Prize winner, Cesar Milstein, who made these so-called monoclonal antibodies, which have revolutionised medicine and saved, you know, hundreds of thousands of lives. And so, I was in Cambridge at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology for about 10 years, actually.

I then went back to medicine and went into industry developing cancer drugs and then into biotechnology. I was involved with editing the first human genome in a living person, you know, targeting rare diseases and things like haemophilia with gene therapy. And then I formed my own company to bring together these incredible technologies, the ability to design DNA and write DNA. My inspiration, I think, dates back to my childhood. When I was around six years old, I was sick in bed. And I very clearly remember my dad coming to my bedside and saying, you know, Adrian, the human body is the most complicated machine in the world. And I remember thinking, wow, you know, more than a TV set even? What is this, you know, complicated biological machine? So, I think my whole life, I've been wanting to understand how the human machine, if you like, works. And how does that relate to the mind and how do the body and mind work together and why do we get ill? So that's always been my driving force and my fascination.

Who are the scientists in this field who have inspired you the most and why?

Oh, in this field. Well, there are lots of brilliant people. You know, there's Jason Chin in Cambridge, who, along with my co-founder Kaihang Wang, wrote the genome of a synthetic bacterium, an E. coli. Not only did they write it out but they also changed the genetic code, the actual way in which amino acids connect with DNA, the code, if you like, of which amino acid is brought in. Then there's Jef Boeke in New York, who's leading the Synthetic Yeast Genome Project, which is an international consortium, and they're close to writing the genome of a yeast. And the yeast genome is 250 times smaller than a human genome. The cell of a yeast is much like our own. It's a eukaryotic cell. It has a nucleus which houses the DNA. It's not like a bacterium, which is a prokaryote; yeast is part of our family of life. So, if we can make a synthetic yeast genome, we're well on the road to making all the other animals in their animal kingdom.

What kind of a timeline are you envisaging for building the whole human genome? And understanding it as well?

Ah, to build a human genome. Okay, so the two questions. So, one is when will we understand the human genome? And the other is when we'll be able to write one, right? I would say, I think within a century, we'll know pretty much everything we need to know about how nature generates the kind of humans that we're, you know, familiar with. And then the second question, writing a human genome. Well, I think that's a very, very tractable problem. As the famous Nobel Prize-winning scientist Peter Medawar has said, science is the art of the soluble. And I would be surprised if we hadn't completed the synthesis of a human genome within two decades.

Now, you may then say, why? Why would you want to build a human genome? Two reasons. One is because we use cells, human cells, for cell therapy to treat patients with cancer and Alzheimer's and autoimmune diseases. So, if we were able to write a version of the human genome that was optimal for cell therapy, that could be very useful medically. And second, if we can write out different versions of the human genome, it will help us to understand how genes cause disease and how the environment interacts with genes. And that will be part of the process of understanding the grammar of life that we were just talking about, which I estimated within 100 years we will fully decode. But I do believe a synthetic human genome is coming at least within 20 years, maybe even faster.

So, in your book, you know, you write about a world where heredity will become redundant. That will solve for us the whole problem of identity-based politics. But at the same time solutions derived from genetic engineering, like cures for all or most diseases and immortality, will be unreachable for the masses. You are writing about two worlds, natural and artificial, interdependent and mutually supportive, existing firewalled from each other, but won't this result in their extinction and the extinction of all purely natural human beings?

Gosh, well, Sucheta, you've asked so many interesting questions that I feel like we could discuss this for probably three days, but I have to give you a concise answer, so I'm going to try to answer some of these things. But, well, first of all, my hope is that natural life will continue pretty much as it is. And if you read my book and my manifesto for life in the final chapter, you'll see that one of my reasons for wanting to turn biology into a programmable material that can be used to build our infrastructure is so that we can preserve natural life and stop destroying the world and creating, you know, pollution with microplastics and so on.

We need to honour life. Natural life is sacred. It's precious. And I'm totally aligned with those monks in India who don't tread on ants. And I don't tread on ants. I never kill insects unnecessarily. You know, when we have a spider in the house, my wife says, kill it, you know, kill it. And I say, no, I'm going to pick it up and I'm going to gently throw it out of the window. So, I want to give it a chance to live. I value nature.

I value life. It's precious. It's sacred, right? So, biology, however, is an alternative material that can create sustainability right now.

And yet, imagine that instead of evolution determining our nature, that governments determined our nature. Now that would be really, really scary and worrisome.

You can imagine that in 100 years, if we did fully decode, you know, the instruction manual, if you like, for human nature, that some governments might say, oh, you know, this empathy thing, it's really unnecessary. We don't want our subjects to have empathy when they, you know, when they invade other people, civilisations on other planets or on Earth, or this thing called free will. You know, it's a terrible disease. We must we must eliminate it. Or, you know, these things called elections and politics and why do they exist? You know, we know what the right way is. And I think and I'm talking about the distant future here, right? But we have a responsibility to think about the distant future. It's not obviously something relevant today, but I think in the future, and I've written my book to be relevant to all points of human history, and I hope in 100 years’ time people will be reading it and they say, wow, this guy Woolfson actually pre-empted this. He realised that human nature, as we know, may eventually be at risk if governments can determine, you know, the sequences of our genomes. And even more scary, perhaps, is the notion that AI might deliberately alter our genomes and design them in ways which make us subservient to it. You know, so the AI is kind of controlling us and we become its agents, right? And that's also a possibility because our minds aren't able to grasp the complexities of genomes. We need AI's help.

And although AI can help us design genomes, we don't really understand how it does it. That's the truth.

Yes, but do you think that we can have a sentient or conscious AI? I don't think we can.

Well, that's, you know, that's a really interesting question and it's deeply philosophical and it goes back to people like Turing, you know, like if something behaves as if it's conscious, is it, does it really matter if it isn't and how would you know it wasn't? Do you know what? I don't honestly know the answer to that, but what I can say is that the intelligence that AI is able to produce will hugely exceed our own, to the extent that human intelligence, as it is today, may become irrelevant.

You know, we may be lucky if AI keeps us as pets, you know, to entertain itself, but we will struggle. Maybe the only way humans or biological beings will be able to remain relevant is by considering upgrading a little bit, you know, maybe not on nature, but just our cognitive performance. Now, let me be really clear about this. I'm not advocating this. I'm merely speculating. I'm just exploring a line of thought, so to speak. But imagine that we got to a point where the AI was so powerful that humans got together and said, look, this AI thing is out of control. It's kind of marginalising us. We're being trivialised. We need to fight back, right? We need to improve our own cognitive power so that we can combine intelligence with morality, right? And agency and all the things that make us human, right? So hey, what we're going to do, we're going to use genome writing, if we're able to, to kind of boost our cognitive capacity so that we can do some of those things that AI does. But unlike AI, which is kind of dissociated from all the things that make us moral agents.

So, I think morality has a chemical basis in terms of the fact that morality is actually, you know, reason guided by emotion, something like that. As in, it involves the processing of emotion and then that emotion serves as the guide to your job of mapping out of the next course of action. And that emotion has got a chemical basis, and that cannot be married into AI. And therefore, we cannot have a conscious AI. That is my thinking. Am I wrong?

Yeah, well, but the thing is, what you've got goes to one level of abstraction. So, yes, you're right that we are built using one particular technology, which is chemistry, right? But beneath the chemistry, you've actually got a process, an algorithmic kind of logic. But it may well be that the logic of emotions can be realised in different substrates. So maybe you can get a synthetic entity like an AI to genuinely experience emotions and a sense of self. And I'm not saying that's possible, and it may not be possible, because it could be that, you know, consciousness is an epiphenomenon of biology, and it can't be generated in any other substrate. But I'm not sure that that's the case as of right now.

And, you know, it's something that would need to be falsified.

And also, of course, as Turing said, you know, if AI behaved as if it were conscious, we may never know if it really is because it mimics consciousness so efficiently. And you could argue it at that point may become irrelevant. The question of whether it is conscious may become irrelevant if it acts as if it is. But I think it is relevant because, you know, a conscious agent, a truly conscious agent, is underpinned by certain values and emotions and morality.

And that's what makes us human, and that's what AI lacks.

Because AI is so energy-intensive and climate change being already upon us, could we perhaps use this new technology to create climate-resistant human beings in the future?

Oh, God. Well, actually, probably you could, but I'd rather we actually dealt with the problem itself, right? And of course, as we know, there's some people who deny that climate change is happening. I'm not one of them, by the way, right? But one of the reasons, you know, I believe that biology and the ability to engineer it is so important is I think it can help counter climate change and the destruction of the environment and the destruction and extinction of Earth species. And that's because pretty much all of the infrastructure that we currently build in a destructive way could actually be built using biology. So, we could actually store much of the world's information in a sustainable way in DNA sequences. We could compute using biology, biocomputers.

We can make green energies, you know, bio-energies using engineered biological organisms. You can make materials using biology like spider silk, for example, has the tensile strength of steel and many other such materials could be built into everyday life, right? So, in addition to all the impacts on healthcare, biology could help counter climate change by reducing our dependence on fossil fuels, and destructive processes. And actually, I would love to see the vision of E.O. Wilson, the zoologist and biologist, realise, which is that half of the earth is returned to wilderness. You know, it's just left to nature. And I would love to see that. And that would involve a degree of population control, but also more efficient production of crops.

But I believe that by really leveraging biology as a technology, we can make a massive contribution.

And what a wonderful vision that is! I wish I could ask you a last question, though, and you have covered almost everything, but what is your message to other technology companies around the world, especially those that are working with AI?

Yeah, I think, my main message to people working in AI is to just have a think about the societal consequences of what you're doing, because the rate at which AI is accelerating is exponential.

And I don't think there's ever been a technology in history as disruptive as AI and a technology which has evolved so rapidly and is so consequential and impacts the means of production on planet Earth. I mean, you know, people need to work, they need to have an income, and they need to have a reason to live.

And we all know that AI is going to dramatically impact that. And everybody in the world is going to be impacted. Now, you know, when I'm in San Francisco, which is where I live, we've got these driverless cars there. And I come to London, which is where I am today. And, you know, the taxi drivers here are blissfully driving around totally unaware that in around two years’ time or maybe less, they're going to be out of a job. What are they going to do?

And it’s not just what we call blue-collar jobs. What about all the jobs that AI is going to take in medicine and law and education? What are those people going to do when AI takes their jobs? And guess what?

Very few people are going to be taking all of those resources, all of the revenue, and it's all going to be going to them. So, you know, what's going to happen is you're going to get these incredibly wealthy people who are drawing on the whole world's resources at the expense of everybody.

And, you know, I don't want to get into politics because I studiously avoid that, but I do think one has to talk about that.

Capitalism is a great kind of mechanism for running a society, because it creates competition and it gives incentive and it kind of stimulates innovation and rewards innovation. And it's always worked pretty well, although it creates, sure, it creates asymmetry. But within that asymmetry, there's always been a place for workers. But I think what's happened now is with AI is that suddenly you're destroying the lower rungs of that ladder. And this is where capitalism, as we know it, breaks down, right?

Because suddenly, there's no protection mechanism for these people. And I think a world in which huge numbers of people are unemployed is a volatile, unpredictable and unstable world. This to me is the key existential issue that AI needs to contend with and that governments need to legislate around. Because, you don't want to lose those key tenets and philosophical principles of capitalism.